By Peter J. Nash

February 5, 2015

| Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  |

Last week, Allan H. “Bud” Selig officially stepped down as Baseball’s czar and passed the reins to his hand-picked successor, Rob Manfred. Selig served as MLB’s ninth Commissioner since the office was created in 1920 by Garry Herrmann’s National Commission and in stepping down he gives up an annual salary of over $22 million–that’s about 440 times greater than Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ $50,000 salary to clean up the 1919 Black Sox scandal. To put it in perspective, Selig’s compensation as MLB’s head honcho for just one season about equaled the record-breaking $29 million fine Landis leveled as a Federal Judge against Standard Oil and John D. Rockefeller in 1907 . Baseball has been very, very good to Bud Selig. So good, in fact, that some sources list his current net worth at $400,000,000. Not bad for a guy once ridiculed as a disheveled used car salesman from Milwaukee and not bad for baseball owners who have seen their annual revenues rise from $2 billion to $9 billion under his watch.

Although he’s retiring from his MLB post, Selig isn’t leaving the game for good and will still rake in $6 million a year as a special adviser to Manfred as “Commissioner Emeritus.” A good portion of the 80-year old Selig’s new duties will likely revolve around legacy building, a process which the former Milwaukee Brewers owner had already kick-started as his days as Commissioner were dwindling. As Rob Neyer writes at FoxSports, Selig isn’t fond of criticism and in the past has phoned writers who have called him out on a variety of issues. He’s also been known to apply pressure on other writers who Neyer says were “told by their bosses to take it easy on the poor old Commissioner.” Now that he’s relinquished his power, Selig wants to make sure that he’s remembered as one of the game’s immortal executives.

Back in 2011, Selig announced he’d be establishing a sports history department at his alma-mater, the University of Wisconsin, and that he’d also spend time on campus to write his memoirs. More recently he’s enlisted the services of his good friend, Doris Kearns Goodwin, to insure that his life-story is in capable hands but Selig’s legend won’t be complete without one last lifetime honor that has eluded even Marvin Miller. Unlike Baseball’s pioneering labor reformer, however, Bud Selig is actually on the fast-track for enshrinement at Cooperstown despite his failures. As he leaves his MLB post only a few writers have been critical of his reign and have said “good riddance” to him like Rolling Stone’s Dan Epstein. On the contrary, Selig is for the most part being hailed as baseball’s “great reformer” by the likes of Jon Heyman at CBS Sports and the “greatest Commissioner of all-time” by Bill Madden.

With all of the accolades being heaped upon Selig recently we thought it would be interesting to gauge his legacy and career as Commissioner by examining the artifacts and memorabilia issues that were generated during his tenure. Can the memorabilia tell us more about Selig and his legacy than some of the card-carrying members of the BBWAA can?

The most obvious artifact linked to Selig’s legacy is the trophy he most recently presented to now-retired Yankees Mariano Rivera and Derek Jeter. When Selig appeared with the hardware at the 2013 World Series he gazed into the gleaming silver and gold Tiffany & Co. trophy bearing his name and then presented Rivera with the “Commissioners Historic Achievement Award.” As Selig glanced away from the trophy he looked to Rivera and said, “Whether they like it or not, players are role models–they are. And can you imagine for this generation, this is our role model.”

The trophy represented what Selig described as a special recognition of Rivera’s “major impact on the sport” and his “contributions of historical significance in Major League Baseball.” For Selig, the award meant even more as he was turning his attention to defining his place in baseball history and his presentation of his own award reinforced his preoccupation with curating his own legacy as he told reporters, “In the life of a Commissioner you have a lot of good days, bad days, whatever, and I can tell you how much this has meant to me and this is for me a very special day.” When Selig presented Mariano Rivera with the trophy he told the closer, “Thanks for all the class and all the dignity.”

Some of Selig’s detractors have argued it is both class and dignity that have eluded both MLB and the Commissioner during his tenure and considering the past recipients of Selig’s “historic” trophy include Steroid-Era cheats like Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa, Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, its hard to make a case for Selig’s integrity being fully in tact. His choices of Rivera and Jeter as the last players to receive the award he created are indicative of Selig’s desire to distance himself from his past decisions and associate himself with players who had never been questioned as PED-cheaters.

Clik here to view.

Selig presented his first trophy to Mark McGwire for reviving the game in 1998 and his last to Derek Jeter in 2014. Selig colluded with his fellow owners in the 1980's and Commissioner Fay Vincent was critical of his theft from MLB players.

That being said, Selig can only hope that his record as Commissioner in the Steroid-Era will be whitewashed the same way his involvement as a complicit team owner in the collusion conspiracy of the 1980s was. Selig and his fellow owners, under the watch of Commissioner Peter Ueberroth, were found guilty of colluding with each other to keep player salaries down and their wrongdoing prompted an arbitrator to award $280 million in damages to the free-agent players. The collusion saga prompted the next Commissioner, Fay Vincent, to read Selig and his fellow owners the riot act. In an interview with Hauls of Shame last week Vincent recalled, “I laid it out to them and told them they stole $280 million from the players and got caught and that the Union got stronger because of it. But not one of them to this day, including Selig, ever admitted what they did. So it’s no surprise that today collusion is basically forgotten.” In the aftermath of collusion and after Vincent introduced a memorandum setting forth MLB’s drug policy, including illegal steroids, Selig conspired again with his fellow owners in true Machiavellian fashion spearheading the ousting of Vincent and the appointment of himself as “interim Commissioner” in 1992.

Ironically, Selig today uses the excuse that he couldn’t fight or expose PED-cheaters because the Marvin Miller influenced Players Union fought testing so vehemently, but very few writers today (besides blogger Murray Chass) follow up that claim and point out that Selig and his owner-partners were responsible for that circumstance as a result of their greed and unfair treatment of their employee-players. Undoubtedly it was Selig and his fellow owners who set the table for the Steroid-Era. Fay Vincent recalls, “Most people forget that back then the owners controlled all labor negotiations and that Committee was headed by Bud Selig, even before he became Commissioner.” Today, Vincent still recalls how hard it was to push drug testing after collusion. “I couldn’t even get Steve Howe removed after eight drug violations because the Union had became even stronger,” said Vincent. As for the Union finally conceding to testing in the aftermath of the Steroid-Era Vincent added, ”It wasn’t until after steroids were out of control that Don Fehr gave into testing because he saw that Congress was going to step in.”

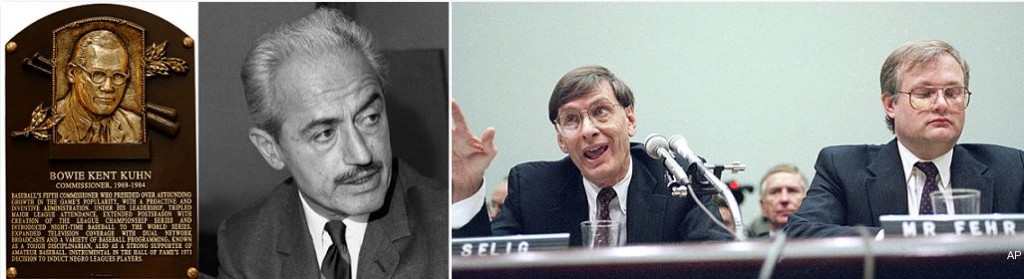

When looking at Selig’s place in history an argument can be made that he has much more in common with the notoriously cheap and devious owner of the Chicago White Sox, Charles Comiskey, than he does with Fay Vincent, Bart Giamatti or even Judge Landis. Interestingly enough, it was another White Sox owner, and Selig’s closest ally, Jerry Reinsdorf, who provided the arbitrator with the smoking gun to facilitate the $280 million collusion award to the players—a memo he sent to owner Bill Giles showing in detail how he colluded in a proposed deal for player Lance Parrish. Today, Fay Vincent views Selig’s legacy differently but feels he will soon join the “Old Roman” Comiskey in Cooperstown. Vincent told us, “It will happen soon, Bud will get into the Hall of Fame right away. But what people should be questioning is this. What is the standard for the induction of a Commissioner? With Bowie Kuhn in the Hall it looks more like a popularity contest.”

Marvin Miller told Vincent as much just before he passed away. The ex-Commissioner recalled, “It was very sad. Marvin told me, ‘Fay, don’t feel sorry for me. I don’t really care. I’m never going to get 3/4 of the vote. Baseball is vindictive and the players will end up forgetting what I did.’ Marvin knew he wasn’t popular enough to get in. Bud’s got the support of the voters.” Selig also has the support of Hall of Fame operatives like Bill Madden who have even suggested that Miller lacked “character” and “integrity” and that he “all but sabotaged his Hall of Fame-worthy career by refusing to help baseball get rid of steroids.”

As Selig exits the MLB stage, numerous baseball writers and sympathetic MLB mouthpieces are remembering everything positive he’s done for the game but have largely ignored his role in collusion and given him a pass on PED’s focusing solely on the game’s record financial growth. It’s difficult to argue with their observations as ballpark attendance, which dipped by 20 million fans after the strike in 1994, has jumped back up to and surpassed the 73 million mark in 2014. But in terms of real growth in attendance figures, Selig has merely restored attendance figures to what they were the year before the Player’s Strike in 1994. In 1993, MLB saw 70,256,459 fans pass through turnstiles and twenty-two years later 73,739,622 fans went to the ballpark in 2014.

Bud Selig’s legacy, however, is much more difficult to define than by just calculating MLB Advanced Media revenues and ticket sales. Oddly enough, baseball historians can take a close look at Selig’s relationship with the baseball artifacts and memorabilia during his tenure to get a different perspective on his reign as Commissioner. Some might even say that the Tiffany and Co. silver trophy he created is a tangible symbol of Selig’s own complicity in compromising the integrity of the game itself.

Clik here to view.

Bud Selig presented the trophy he created to Mariano Rivera during the 2013 World Series. The Hall of Fame's collection includes the trophy presented to Lou Gehrig by his teammates on "Gehrig Day" in 1940

Players and Commissioners fade away and die, but the trophies and trinkets associated with their carreers survive and sometimes end up in Cooperstown. There’s Lou Gehrig’s trophy presented by his teammates on “Gehrig Day” in 1941 at one end of the spectrum and Eddie Cicotte’s 1917 World Series uniform emblem and pocket watch on the other. The artifacts themselves sometimes reveal more about the historical subjects than the contemporary accounts published in newspapers. If the “Commissioner’s Trophy” presented to Mark McGwire is ever put on display at Cooperstown it will no doubt say more about Selig’s legacy than writers could ever express in print.

Although Selig won’t be able to spin-doctor his long-term legacy from the grave and will be critically exposed by future historians like Judge Landis has, it appears that while Selig is still living his legacy is largely secure and he is already said to be a shoe-in for the Hall of Fame. All indications point to Selig being honored in Cooperstown with a bronze plaque hanging right next to Bowie Kuhn’s while Marvin Miller will continue to be shut out. And speaking of the legacies of Miller and Selig, a source close to the Player’s Union speculates that another chapter in Selig’s story may one day emerge showing how his operatives pressured HOF Veterans Committee voters in private not to cast their ballot for Miller while supporting his induction publicly.

Back in 2011, SBNation’s Grant Brisbee noted that the trophy Selig created resembled a “big ol’ you-know-what” and that players receiving it were, in fact, getting the shaft, literally. He asked, “Is the award emblematic of how out of touch Selig is, or somehow poignant in its irrelevancy?” Or is the award a symbol in the Post-Steroid Era of what Brisbee called, “A reminder of just how naive most of us were” as McGwire and Sosa juiced up and saved the game, just like Babe Ruth had after the Black Sox scandal in 1919? Selig’s supporters note that the game has experienced unprecedented financial growth and record revenues under his tenure, but wasn’t most of that record growth the direct product of McGwire and Sosa saving the game during the “March on Maris” in 1998?

Clik here to view.

Mark McGwire memorabilia arrived at the HOF with much fanfare in 1998 (left). Todd McFarlane paid $3 million for McGwire's 70th HR Ball (center). Barry Bonds' record breaking ball was donated to the HOF with an asterisk added to it (right).

Selig, in fact, hatched the scheme to commission his trophy at Tiffany & Co. in 1998 with Big Mac and Sosa slated as the first honorees after both were widely credited with reviving baseball after the devastating strike in 1994. For Selig and his fellow MLB owners, the hitting exploits of McGwire and Sosa got the turnstiles at MLB ballparks humming again and filled up MLB’s cash coffers at a record clip. The Home-Run mania also shifted the focus away from fans vilifying Selig for the part he played in the game’s labor woes. How could Selig not honor the two living legends who were already being honored in the “Great Home Run Chase” exhibits installed at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown? It also wasn’t lost on Selig that he’d been booed at every Hall of Fame Induction ceremony since the strike. Caught up in the home run hysteria, Selig was McGwire and Sosa’s biggest cheerleader and he exploited their accomplishments accordingly.

When McGwire’s 70th home-run ball went up for auction in 1999, comic-book icon Todd McFarlane bought it for over $3 million as the most prized baseball artifact of all-time but in just fourteen years the value of the ball has plummeted drastically. Memorabilia experts say the ball isn’t even worth $100,000 today. In 2010, even McFarlane acknowledged the depreciated value of the McGwire ball when he told the Chicago Tribune, “It’s like a car that loses its value the minute you drive it out of the lot — well, I just crashed the car. But people are still going to want the car James Dean was driving in when he got killed. So it’s still cool. It’s infamous.” In its infamy, the McGwire ball might just be the single artifact that defines Selig’s legacy moving into the future.

Clik here to view.

Recipients of MLB's Commisioner's Trophy for Historic Achievement have included (clockwise): Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa; Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds. A-Rod was on his was to winning one but MLB's probe into his relationship with PED dealer Tony Bosch stood in the way.

The McGwire ball and the presentation of Selig’s trophy to “Big Mac” also serve as a link to another recipient of the award, Barry Bonds. Bonds was honored in 2002 after breaking the single-season MLB Home-Run record set by McGwire in 1998 and, at the time, was well on his way to breaking the all-time Home-Run mark held by Selig’s close friend and former employee Hank Aaron.

McFarlane also purchased the ball hit for Bonds’ 73rd record-breaking home run for $450,000. Oddly enough, Selig didn’t present a “Historic Achievement Award” to Bonds for breaking Aaron’s milestone. Selig and Aaron are close friends and sources indicate his relationship with Aaron greatly influenced his unprecedented investigation into Alex Rodriguez. A healthy Rodriguez could have made a run at Aaron’s and Bonds’ all-time home run marks but his 211-game suspension last season has made that an impossibility.

There’s no shot that Rodriguez will ever take home a Selig trophy for his career achievements the way Roger Clemens did before he was implicated in the Mitchell Report. A-Rod will never get his hands on the trophy that Selig has also presented to Vin Scully, Ichiro Suzuki, Roberto Clemente (posthumously), Rachel Robinson and Ken Griffey Jr. All things considered, after Griffey received the award from Selig at the 2011 World Series Craig Calcaterra of NBC Sports called the award “baseball’s version of a gold watch to notable players.”

Clik here to view.

MLB's history with Tiffany & Co. dates back to the creation of the "Hall Cup" in 1888 and extends to the re-design of the current World Series Trophy by Tiffany in 1999 (center). Selig's "Historic Achievement Award" was created by Tiffany in 1998 for Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa.

Baseball’s historic awards and trophies have run the gamut of everything from Gold Gloves to Silver Slugger bats and represent greatness for players who take home the Cy Young awards and League MVPs in the course of their careers. The ultimate prizes in the game, however, have always been awarded to teams winning the World Championship dating back to times before a World Series even existed. Baseball’s history with Tiffany and Co. dates back to 1888 when the company was commissioned to create the “Hall Cup” awarded to Jim Mutrie’s New York Giants as the winners of the National League Championship. It wasn’t until Selig got the idea to create his own Commissioner’s “Historic Achievement” trophy that MLB also re-connected with Tiffany to re-design the Commissioner’s World Series Trophy as well. The Hall Cup is currently on display at the Baseball Hall of Fame in the World Series exhibition room.

Just as the Hall Cup has made its way to Cooperstown, so will Selig’s silver-shafted trophies as future generations of fans will be able to decide for themselves whether Selig was an enabler or a crusader in both the Steroid and Post-Steroid-Eras. Of course, the memorabilia that made its way to Cooperstown during Selig’s tenure is tainted and in retrospect it’s an embarrassment that the Hall of Fame dedicated its plaque gallery to a special exhibition including McGwire and Sosa’s bats, balls and uniforms in 1998. It’s even more of an embarrassment for Selig and MLB that Barry Bonds’ record breaking baseball arrived in Cooperstown with a big asterisk carved into the cowhide–compliments of designer Mark Ecko. And it was Selig who orchestrated the $8 million purchase of artifacts from Yankee partner Barry Halper’s collection in 1998 only to find out nearly a decade later that several of the big-ticket items he purchased, including “Shoeless” Joe Jackson’s 1919 road jersey, Jackson’s “Black Betsy” bat and Mickey Mantle’s 1951 Yankee rookie jersey were poorly executed forgeries that were fraudulently displayed for millions of fans.

Clik here to view.

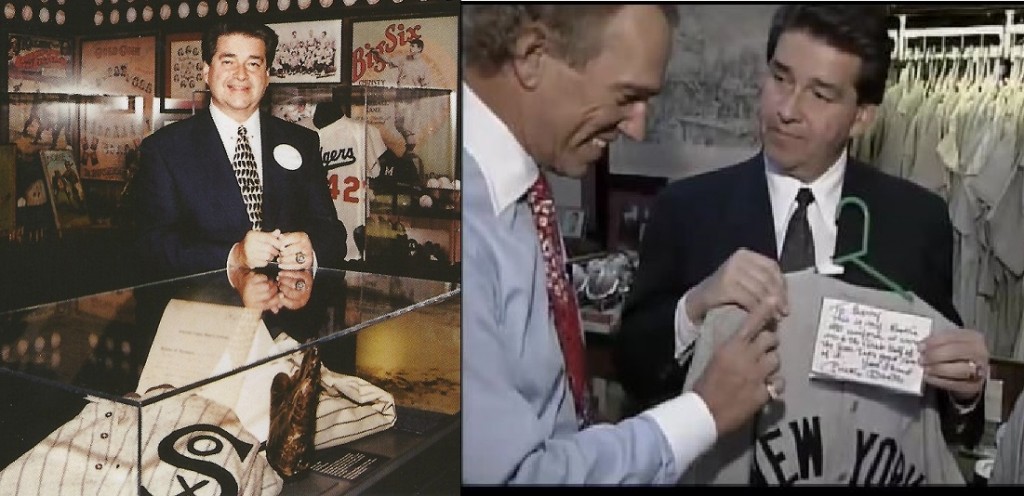

Bud Selig helped orchestrate MLB's purchase of $8 million in memorabilia from Barry Halper including a fake 1919 Joe Jackson jersey (left) and a fake 1951 Mickey Mantle jersey (right).

Neither Selig’s office nor the Hall of Fame conducted any suitable due diligence to ensure that the items they were purchasing from Halper were genuine. Halper lied to them saying he purchased his Jackson items from his widow in the 1950s but Selig & Co. could have read The Sporting News at the National Baseball Library to learn that Halper told Bill Madden he’d acquired the jersey from Jackson relatives as a “recent purchase” in 1985. Madden, however, never mentioned that information when he reported MLB’s purchase of Halper’s trove in 1998 for the New York Daily News. After Hauls of Shame published a report in 2010 illustrating the Jackson jersey was a fake and attributed to the wrong White Sox uniform manufacturer, the Hall revealed they had sent the same garment out for testing and found that the jersey was constructed with materials that didn’t exist during Jackson’s MLB career. While Bud Selig had continued MLB’s “lifetime ban” of Joe Jackson into the afterlife, he also succeeded in facilitating the entry of his fake jersey into the hallowed Halls of Cooperstown.

Clik here to view.

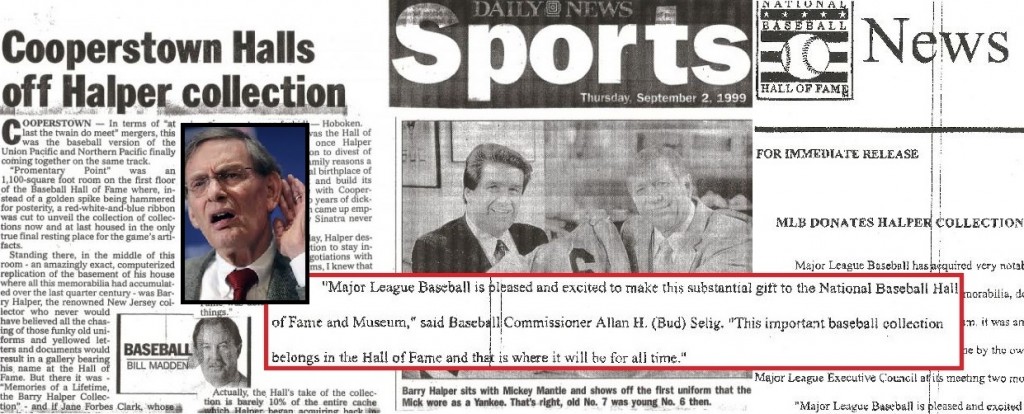

In 1998 Selig and MLB purchased several million dollars in fakes from Yankee partner Barry Halper and donated them to the HOF. The fakes were heralded by Bill Madden in the Daily News and in an MLB press release Selig said Halper's items would be in Cooperstown "for all time."

When Selig and MLB purchased Halper’s alleged treasures in 1998, the Commissioner’s Office issued a press release in which Selig stated, “This important baseball collection belongs in the Hall of Fame and that is where it will be for all time.” In line with Selig’s sentiments, Halper was also honored by Hall Chairman Jane Forbes Clark with a permanent museum exhibition space named after him and a plaque honoring him for his “dedication to preserving baseball history.” After Halper’s fakes were exposed in numerous published reports the man who Selig and his fellow owners helped oust from the Commissioner’s Office years earlier weighed in on the scandal. Fay Vincent, MLB’s former commissioner and an honorary director of the Baseball Hall of Fame, said, “Given the evidence that has come to light in the past several years, the Hall of Fame should immediately reconsider the naming of that gallery to honor Barry Halper. I do not think he deserves the honor.” By the time Vincent’s statement was published by Deadspin in July 0f 2011, the “Halper Gallery” and the plaque honoring the now deceased Yankee partner had been removed from the Hall’s floor plan.

Clik here to view.

Jane Forbes Clark (left) dedicated a research center at the HOF to Bud Selig (center) but neither Selig, MLB or the HOF have taken any action to recover documents stolen from the August Herrmann Papers collection (right).

Just as the Halper Gallery vanished, Selig was working with the Hall of Fame to establish a “Commissioner’s Research Center” at the Bart Giamatti Research Center in the National Baseball Library. When the ribbons were cut for the alleged “center”, however, former Hall of Fame employee Gabe Schechter published a piece exposing that the dedication of the space was just “for show” and only a symbolic gesture from Hall Chairman Jane Forbes Clark for “her Commissioner” who had chosen to hold the “‘Winter Owners’ Meetings” in Cooperstown. As Schechter noted on his blog, the ceremony gave “each party a chance to suck up to the other” and added, “The Hall of Fame, having finally shed the Doubleday Myth, managed to create another one with the dedication of an empty, inaccessible space in honor of Selig.”

Of the “Research Center” Clark said: “The Selig Center for the Archives of Major League Baseball Commissioners” will ensure a permanent home for the documentation and preservation of the Office of the Commissioner’s contributions to baseball history. This archive will provide a central location for the study and research of the importance of the Office of the Commissioner, and its role in shaping and advancing the National Pastime for nearly a century.” The great irony, here, is that while both Clark and Selig were talking preservation and history they sat back and did nothing to investigate the massive thefts at the National Baseball Library from archives including the papers of former Commissioner Ford Frick and the August Herrmann Papers collection which constitutes the first and most important archive generated by Major League Baseball before the Commissioner’s office was established in 1920. Although there is overwhelming evidence of the thefts and donated materials are being sold at public auctions regularly, neither Selig, MLB Security or the Hall of Fame has taken any substantial action to recover or claim title to the stolen materials. In fact, one source familiar with Hall operations told Hauls of Shame that library employees have been instructed to look for evidence suggesting that items may not have been stolen from the library, rather than pursuing recovery.

Clik here to view.

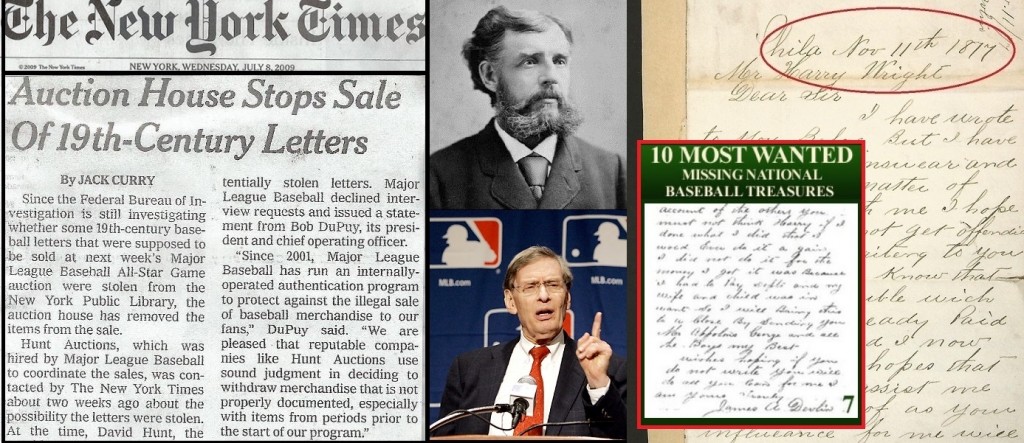

In 2009 the New York Times reported that letters stolen from the NYPL's Harry Wright archive were being sold in MLB's All-Star Game auction. The letters, including a famous letter written by Jim Devlin to Wright in 1877 (right), were pulled from the auction after the FBI opened an investigation.

In addition to standing idle as MLB’s own baseball history was looted from the Hall and peddled off at auction, another memorabilia-themed travesty occurred during Selig’s reign when MLB’s 2009 All-Star Game auction featured over fifty rare documents that had originally been bequeathed to the National League in 1895 by baseball pioneer Harry Wright. The letters were once part of Wright’s personal baseball library and archive which he intended to be a nucleus for a collection devoted to the game’s history, but thousand’s of Wright’s letters were stolen from the New York Public Library after they were donated in 1921 by the widow of ex-National League President A. G. Spalding.

As revealed first in a Sporting News article published in 1977 by Bill Madden, the owner of the stolen archive of Wright’s correspondence was none other than New York Yankees minority owner Barry Halper. Halper brazenly showed off the documents to Madden who identified the treasure trove as once belonging to Harry Wright and in the years that followed Halper sold off the archive for big money at Sotheby’s in 1999, including the sale of a letter presenting Wright and his Boston Red Stockings the 1875 Pennant. That same letter was cited in the works of Dr. Harold Seymour and Dorothy Seymour Mills who later confirmed the document was donated to the NYPL and had been stolen.

The Harry Wright correspondence appearing in the 2009 MLB auction was also believed to have originated with Halper and when the New York Times reported that the stolen letters were pulled from the MLB auction Selig declined comment. Times reporter Jack Curry wrote, “Major League Baseball is in an awkward position of having to explain why it coordinated an auction in which it was selling potentially stolen letters.” Bob DuPuy, MLB’s president and chief operating officer at the time issued a statement saying, “Since 2001, Major League Baseball has run an internally-operated authentication program to protect against the illegal sale of baseball merchandise to our fans. We are pleased that reputable companies like Hunt Auctions use sound judgment in deciding to withdraw merchandise that is not properly documented.”

But after a five-year investigation was conducted by the FBI, the NYPL recovered none of the stolen Wright documents. In fact, the investigators and the NYPL actually allowed the sale of the stolen documents from the Hunt Auctions consignor to a dealer for over $35,000. Two of the historic handwritten letters sold were written by disgraced player Jim Devlin, who was banned from the game by President William Hulbert for his part in one of the game’s earliest gambling scandals. Both of those missives were specifically cited in published works by Seymour and also specifically documented as NYPL property in original research notes now housed at Cornell University.

Historian and author, Dorothy Seymour Mills (who originally helped the FBI identify the letters as stolen property in the 2009 MLB auction) still feels that the NYPL should be held accountable. Mills told us, “If the Harry Wright letters belonging to the NYPL, a great research library, are available, the NYPL should purchase them. Instead, the management has spent the library’s money on the opposite goal: working out a plan to dismantle a large part of its research function. I blame the NYPL for not protecting these valuable documents for posterity.”

Clik here to view.

MLB purchased $125k worth of stolen documents in its A-Rod investigation (left). A dealer recently purchased stolen documents originally willed to the National League by Harry Wright in 1895 (center). Deceased Yankees minority owner Barry Halper owned and sold the stolen Wright documents and has been linked to a 1970s heist at the NYPL.Although they were fully aware of the facts and what was transpiring during the FBI investigation, MLB and Selig did nothing to protect or recover the documents that Harry Wright had originally donated to the National League in 1895. With all of the billions in revenue MLB has been raking in, Selig & Co. couldn't afford the $40,000 to reimburse the current owner of the stolen property and facilitate the return of the archive to its rightful owner, the NYPL. In essence, Harry Wright, one of the pioneers of the game and the "Father of Professional Baseball" entrusted the National League with his archive and the current MLB leadership turned their backs on the commitment that their predecessors had made in good faith.

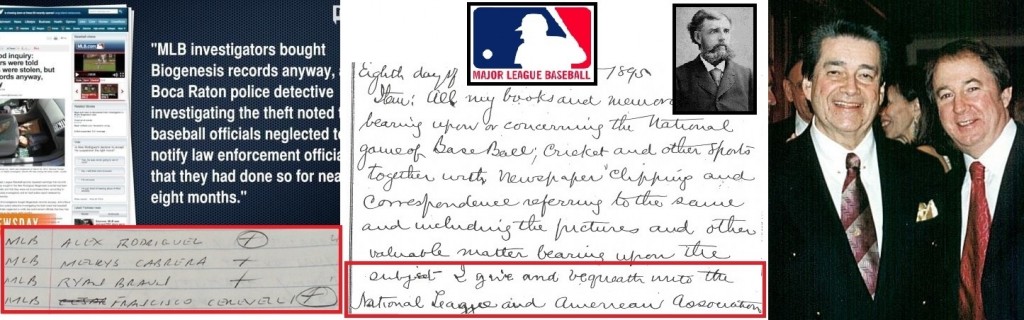

There’s no doubt that Selig and MLB security have the resources to investigate, pressure and rectify such wrongdoing as was evidenced in the Alex Rodriguez investigation. In their pursuit of obtaining evidence against Rodriguez, MLB operatives knowingly purchased stolen documents sourced to the BioGenesis company that supplied Rodriguez with performance enhancing drugs. As reported in the Sun-Sentinel in may of 2014, MLB’s executive vice president of labor relations, Dan Halem, confirmed that MLB “had bought a ‘batch of documents’ on four flash drives” for $100,000. The Sentinel also noted that police reports in Boca Raton, Florida, showed that MLB purchased an additional $25,000 in stolen documents at the Cosmos Diner in Pompano Beach in 2013.

While Selig and MLB can’t be held accountable for the inaction and negligence of NYPL officials like Victoria Steele and Tony Marx, they could have taken the initiative to do everything in their power to restore Harry Wright’s archive to the NYPL. The first step in that process would have been to reimburse the memorabilia dealer who purchased the stolen documents in 2013. But for MLB and Selig, that small investment appears to have been too steep a price to pay. Or was it?

Sources indicate that Selig and MLB are miffed that reports over the past few years have exposed one of their own, Barry Halper, as the biggest fraudster in the history of the memorabilia industry. Selig and other MLB and HOF officials like Jane Forbes Clark have been embarrassed by the revelations that Halper categorically swindled them out of millions and caused millions of baseball fans to pay for admission to Hall of Fame exhibitions touting fake relics like the jerseys of Mickey Mantle, Cy Young and Joe Jackson.

Clik here to view.

Former MLB Commissioner Bowie Kuhn already has a HOF plaque (left) while Marvin Miller (center) has been shut out. All signs point to Bud Selig being inducted to the Hall in the near future.

The Commissioner’s office was previously embarassed when Bowie Kuhn’s right-hand man, Joe Reichler, was caught selling off Hall of Fame property loaned to MLB in 1983. Reichler’s sale of many vintage World Series programs to Long Island dealer Bob Sevchuk was exposed by The Sporting News and Kuhn ended up facing the scrutiny of New York Attorney General Robert Abrams. The Reichler incident was described as a major scandal by The New York Post, but that situation pales in comparison to the multi-million dollar thefts from the Hall’s Frick and Herrmann collections and the NYPL’s Harry Wright archive. Barry Halper’s ownership of large caches of stolen documents was never scrutinized because of his reputation as an MLB insider and minority partner of George Steinbrenner.

Considering the magnitude of the thefts and the failure of the recovery efforts—and the fact that an MLB team minority owner was actually linked to the thefts and sales of donated and bogus artifacts, no Commissioner has ever had a more sordid relationship with baseball artifacts and memorabilia than Bud Selig has.

Clik here to view.

A 2011 New York Post story by this writer detailed the memorabilia fraud of deceased MLB owner Barry Halper (left); Bud Selig said Abner Doubleday "invented" baseball in a 2010 letter to author Ron Keurajian (right).

How history will remember Bud Selig remains largely in the hands of baseball writers and SABR researchers like Dan Epstein. While Selig has fashioned himself as a baseball historian with a soft spot for Abner Doubleday, Epstein and others will likely remind future generations of baseball fans of his entire record in Baseball even if there isn’t much revealing information in his “research center” in Cooperstown. As for Selig’s legacy Epstein told us, “I do believe that Bud Selig was a terrible (and terribly corrupt) commissioner; but this is America, where corporate profits are used as justification (and/or motivation) for everything.” Epstein chalks up the current Selig love-fest to a form of baseball writer Stockholm syndrome and added, “It doesn’t surprise me at all that, given the game’s current rude financial health, Selig would be widely praised as being ‘good for baseball’. And really, he couldn’t have timed his exit better; had Selig left office shortly after the ‘94-’95 strike, the contraction idiocy of ‘01-’02, the move of the Expos to DC or the 2005 steroids hearings, he would be widely considered a failure today.”

As Selig exits the MLB stage, Pam Guzzi, the great-great-granddaughter of the “Father of Professional Baseball” has her own parting shot for the Commissioner. Guzzi, who has been waiting since 2009 to have Harry Wright’s stolen papers returned to the New York Public Library, told us, “With the money MLB pulls in, I find it incredulous that the members are not more willing and active in trying to protect its history and honor the wishes of its forefathers.”

Guzzi is aware that the current owner of the stolen documents is willing to play ball with MLB or the NYPL to facilitate the return of Wright’s letters. The owner, who requested anonymity, told us, “I would accept $35,000 and gladly allow these to be returned to the NYPL via MLB or some other third party. I feel that is honestly about 20%-25% of their “value” since there are two (James) Devlin letters and Harry Wright’s acceptance letter into the Cincinnati Red Stockings.” It is estimated that the fair market value of the cache of letters would be about $250,000 if the items had clear title.

If Harry Wright had not bequeathed his archive the National League in 1895, and his treasure-trove remained in his descendants possession, the Wright family would be sitting on a small fortune worth millions of dollars. Pam Guzzi is frustrated with the NYPL’s failures and Selig’s inaction especially considering the concern MLB expressed in the 2009 New York Times reports. Said Guzzi, “It would have spoken volumes to Selig’s legacy, if he had, although no legal obligation seemed apparent, felt a moral obligation to push MLB to buy the Wright letters and then donate them back to the NYPL. I implore Selig’s successor and MLB to do the right (Wright) thing and get these documents back! If I had the money. I would pay the collector myself.”

Now that Bud Selig’s legacy is being scrutinized, let’s hope that baseball historians in the future remember that when the Commissioner had the opportunity to help recover, preserve and protect the most important baseball archive in existence—he did absolutely nothing.