January 20, 2015

| Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  |

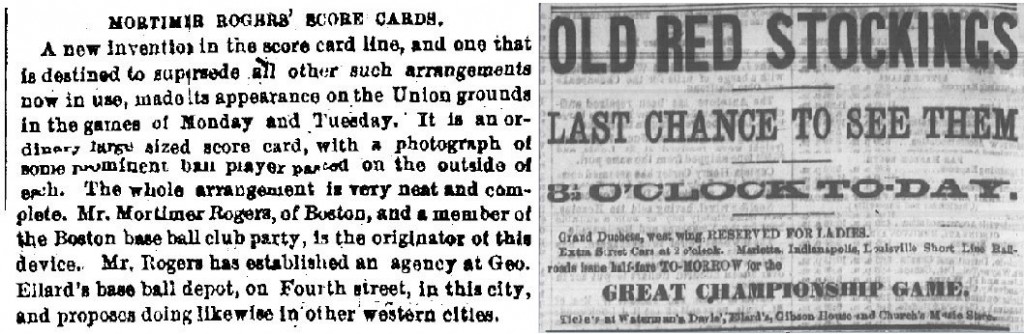

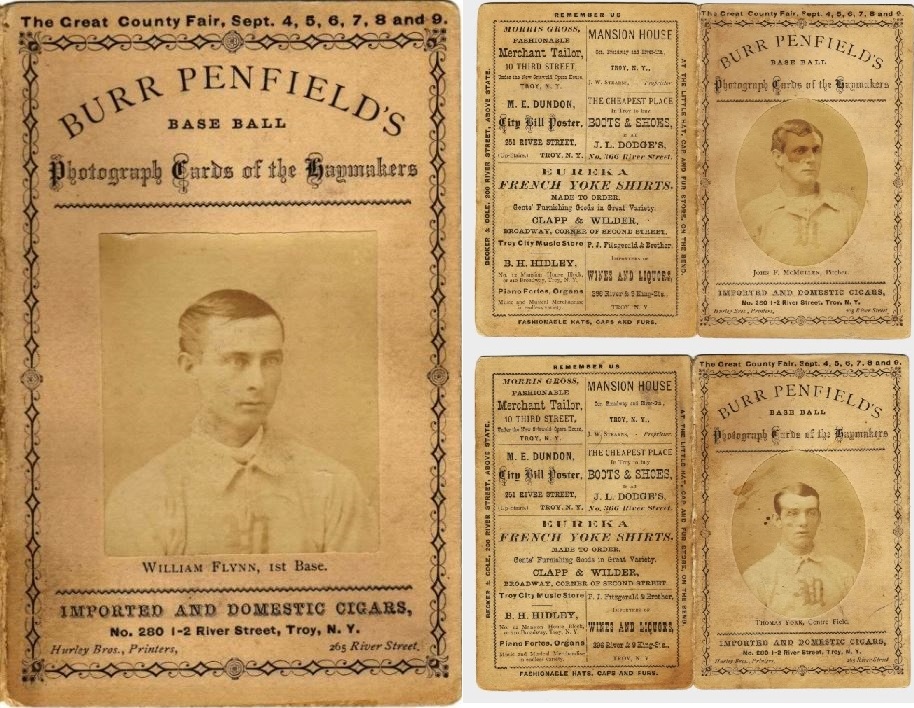

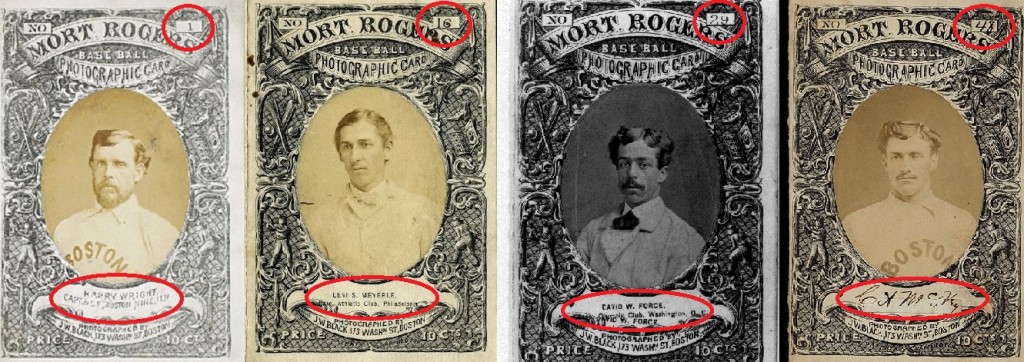

Keith Olbermann recently used the platform of his ESPN telecast to call out Antiques Roadshow appraiser Lee Dunbar for her million-dollar appraisal of a group of trimmed Mort Rogers scorecards featuring portraits of the Boston Red Stockings. In doing so, he echoed the sentiments of the very small group of collectors who either own or have expertise related to the photographic scorecard rarities. However, in criticizing Dunbar’s ignorance about the ephemeral relics, Olbermann also triggered some SABR-spelunking into his own claims on ESPN that a hundred or so Mort Rogers scorecards have survived and stood the test of time.

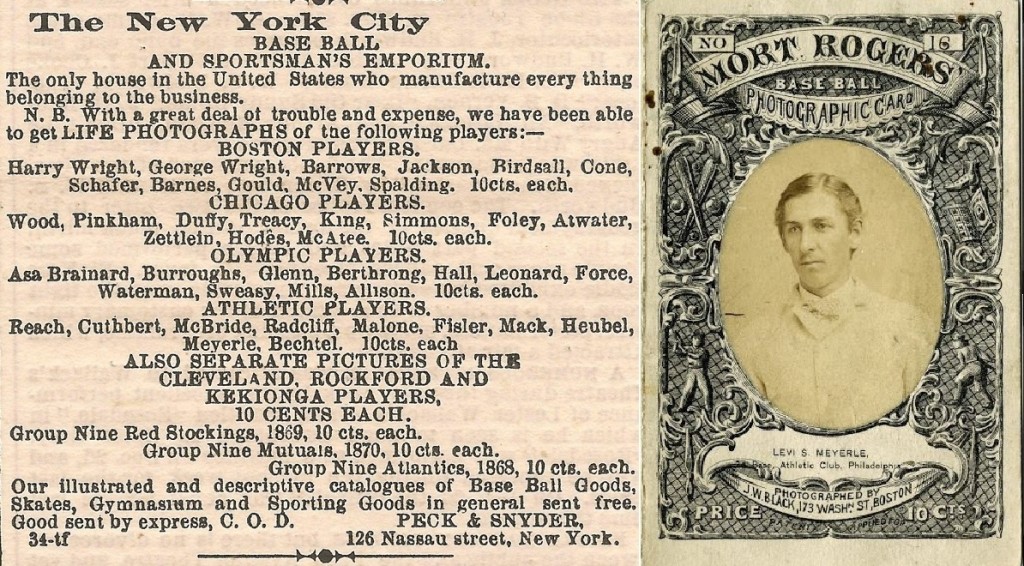

Digging a little deeper into the history of the scorecards, historian and author, John Thorn, inadvertently discovered that Mort Rogers, a 19th century printer by trade, may have created the very first set of cards sold nationally and designed to feature the pictures of every professional baseball player for a particular season. Based on the information Thorn unearthed in 19th century newspapers, it appears that Rogers was far ahead of his time and could very well be considered the long-lost father of the modern baseball card. Another advertisement from the New York Clipper discovered by HOS appears to support that claim and also suggests that his “invention” and its use as a scorecard was secondary as his product was marketed to the public as cards to be collected as a series. Rogers even identified each of his offerings as a “Baseball Photographic Card.”

Two weeks ago Olbermann told his ESPN audience, “There are at least two dozen different ones (Mort Rogers scorecards) known and at least one hundred in total in existence, even I have a bunch-and they’re in all the catalogs.” But based upon the numbers assigned to each card, there appear to be at least four or five dozen different cards created by the enterprising printer. More importantly, however, was Olbermann’s claim that one hundred copies have survived when Hauls of Shame could only confirm the existence of approximately forty-two score cards–not including the “bunch” in the broadcaster’s own collection.

Clik here to view.

HOS research documented 32 images of existing Mort Rogers score cards including the recent find unearthed on Antiques Roadshow (top row left). The other group of 10 trimmed Boston cards that sold in 1992 and 2000 is augmented by unaltered and complete scorecards featuring players from Boston, Philadelphia, Washington and Cleveland. The Baseball HOF has only two examples pictured above of Levi Meyerle and Davy Force.

We contacted several veteran collectors who own examples of the rare scorecards and they were also perplexed by Olbermann’s assertion. One collector said, “Funny, I had the same reaction when I heard Olbermann state there were at least 100 Mort Rogers scorecards known. He said he had “a bunch,” so I suppose he might know something we do not. However, I’ve been following these for decades and would estimate the number known at closer to 50 than 100, more than half of them (with) front covers cut down to varying degrees.”

The collector also informed us that he was aware of about ten examples of the Rogers scorecards that were not included in our grouping of images of documented examples. That would put the verified population of cards at forty-two examples—not including Olbermann’s “bunch” of cards.

The group of forty-two scorecards from games in 1871 and 1872 includes: (10) trimmed Boston cards from the 2014 Roadshow find; (10) trimmed Boston cards sold atLelands in 1992 and REA/Mastro in 2000; (3) complete score cards of Dave Birdsall (Boston), Eugene Kimball (Clev.) and Andy Leonard (Wash) sold at REA/Mastro in 2000; (2) complete score cards of Levi Meyerle (Phila.) and Davy Force (Wash.) in the Baseball Hall of Fame collection; (2) complete score cards of Harry Wright (Boston) and Dick McBride (Phila) in the Boston Athenaeum Collection; (1) complete score card of Cal McVey (Boston) once owned by dealer Jerry Smolin and sold by REA in 2014; (1) complete score card of Dave Birdsall (Boston) sold by Lelands in 2001; (1) complete score card of Harry Schafer (Boston) sold by Lew Lipset in 2000 and believed stolen from NYPLs Spalding Collection; (1) complete Harry Wright score card sold for over $12,000 at Mastro in 2003; (1) complete score card of Count Sensenderfer (Phila.) sold for over $11,000 by Heritage in 2011; (10) additional scorecards identified by a veteran collector (not including Olbermann’s).

If Olbermann actually owns more than fifty Mort Rogers scorecards, more power to him. The broadcaster did not respond to our inquiry as to how many of the 1871 cards he currently possesses. Every experienced collector that we contacted, however, thought Olbermann’s population estimate was way-off, just like Roadshow’s appraisal. That being said, Olbermann’s apparent inflation of the number of the surviving examples would likely be more on point had he made his comments back in 1871 as it appears the scorecard issue actually featured close to one hundred subjects issued in a numbered series. Keeping that in mind and based upon his recent discoveries about the scorecards John Thorn added, “Oddly, Keith’s claim that there were about 100 Mort Rogers cards in existence may yet be proven right.”

Clik here to view.

Surviving copies of the rare score cards of Dave Birdsall and AG Spalding (from the Roadshow find) reveal that player/publisher Mort Rogers (right) sold his wares at the ballpark for 5 cents and 10 cents.

For decades the Mort Rogers scorecards have been a bit of a mystery for collectors. Most of the cards are dated or identified by specific games played in 1871 or 1872 but some examples have a sales price established by Rogers at 10 cents (10c) while one example depicting Boston player, Dave Birdsall, is priced at just 5 cents (5c). The two prices suggest that the 5 cent score cards may have been issued later in 1872 to reflect a price reduction. Another curious feature is that multiple scorecards of the same player use portraits that are slightly different but appear to be from the same photo shoot. Perhaps the biggest mystery is the scarcity of the scorecards as evidenced by the holdings in the Spalding Collection at the New York Public Library. According to the 1922 library inventory for the largest collection of 19th century baseball materials only one score card of Harry Schafer was donated, and that card is currently missing. (A. G. Spalding’s personal scrapbook from the early 1870s is also missing from the collection and it is possible that some other Rogers scorecards were pasted into that volume.)

Each Mort Rogers scorecard is described on the cover as a “Baseball Photographic Card” and on PBS’ Roadshow, Lee Dunbar, described the cards as, “Some of the earliest known 1871 photographic baseball cards.” On ESPN, Olbermann said that the scorecards were so rare because “they didn’t sell that well.” But was that really true? Were they a bust and were the scorecards only sold in Boston at Red Stockings games as hobbyists have long assumed?

That’s where baseball historian John Thorn was able to shed some more light on Mort Rogers’ scorecard business and the process by which he sold them at ball games and other venues. The first discovery Thorn made was a news item published in the Cincinnati Daily Gazette on July 7, 1871, which announced Rogers’ “invention in the score card line” and shows that Rogers not only sold his scorecards at the Boston Grounds but also at visiting ballparks with pictures of the opposing players affixed to the covers. Evidence suggests that Rogers used Boston photographer J. W. Black to shoot the Red Stockings while other photographers around the country may have provided him with portraits of out-of-town players. Working against this theory, however, is the actual graphic on every card which states “Photographed by J. W. Black.” John Thorn also astutely noted that several of the portraits on the scorecards were identical to those featured on the rare team composite CDV photographs which were also issued in 1871 and sold by J. W. Pierce in Chicago.

Clik here to view.

John Thorn unearthed an 1871 report from the Cincinnati Advertiser (left) revealing Mort Rogers' plans to sell his series of photographic score cards in conjunction with a reunion game of the 1869 Red Stockings (right) and a NA game between Boston & Washington. (Courtesy of John Thorn)

The newspaper item Thorn found revealed how the scorecards made their appearance at the Union Grounds on Monday and Tuesday of that week in 1871 and how Rogers had “established an agency at Geo. Ellard’s baseball depot, on Fourth street (Cincinnati)” to sell the scorecards. The paper also announced Rogers’ plans for “doing likewise in other western cities.” During that road trip the Boston team played the Olympics of Washington in the Queen City and players from both teams also participated in a reunion game of the champion 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings. Cincinnati also hosted several other NA games featuring out-of-town teams in 1871 and it is likely that Rogers’ scorecards were sold at each game.

Thorn’s next discovery from the Cleveland Leader was published a week later on July 13, 1871, and confirmed what had been reported in Cincinnati as Rogers sold his cards at the grounds of the Forest City Club of Cleveland. The paper reported, “Mort Rogers, of Boston, now with the club, has gotten out an exceedingly neat photographic score card. This series which he proposes to publish, will comprise pictures of every professional ball player in the country, and will make a valuable collection. This afternoon, score cards with photographs of each member of the Forest City Club will be for sale at the grounds.” Supporting this report is the surviving score card featuring the image of Forest City player Eugene Kimball which was sold by REA/MastroNet in 2000.

Clik here to view.

John Thorn also found a July 13, 1871, report in the Cleveland Leader that revealed Mort Rogers' score cards were sold in ballparks all around the country and were intended to feature the pictures of every professional baseball player. (Courtesy of John Thorn)

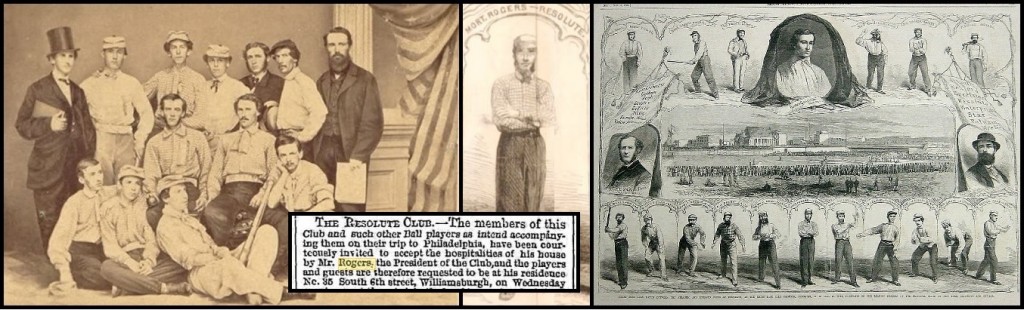

Maxson Mortimer Rogers was born in Brooklyn in 1845, the son of a fish dealer named Albert Rogers Sr., and played his earliest baseball in 1861 as a teenager for the city’s junior circuit Resolute Base Ball Club, which was also known as “Oul man Rogers and Sam Storer’s fish chowder nine.” Early in his career Rogers took on the persona of a jack-of-all-trades as a pitcher, umpire, scorer and club bookkeeper and by 1864 he was appointed the Secretary of the National Association of Baseball Players. Rogers developed into one of the game’s premiere players and a testament to his skill was his inclusion in a famous 1865 woodcut published in Leslie’s Magazine as one of New York’s “leading players” along with the stars of the Excelsior, Atlantic and Mutual ball clubs. Rogers also appeared in another iconic Civil-War era image taken of the Resolutes supposedly during an 1864 tournament in Philadelphia. The group posing with Rogers included notables such as John Wildey of the Mutuals, baseball scribe Henry Chadwick and Philadelphia native Dick McBride who at that time had been granted a furlough from the Union Army to play in the tournament.

Clik here to view.

Mort Rogers was a prominent player in the 1860's and appears (left) as President of the Resolute BBC after a game in 1864 or 1865 vs. Philadelphia. Rogers (center) was also featured in the famous 1865 Leslie's woodcut (right) honoring Jim Creighton and the "leading players" in NYC.

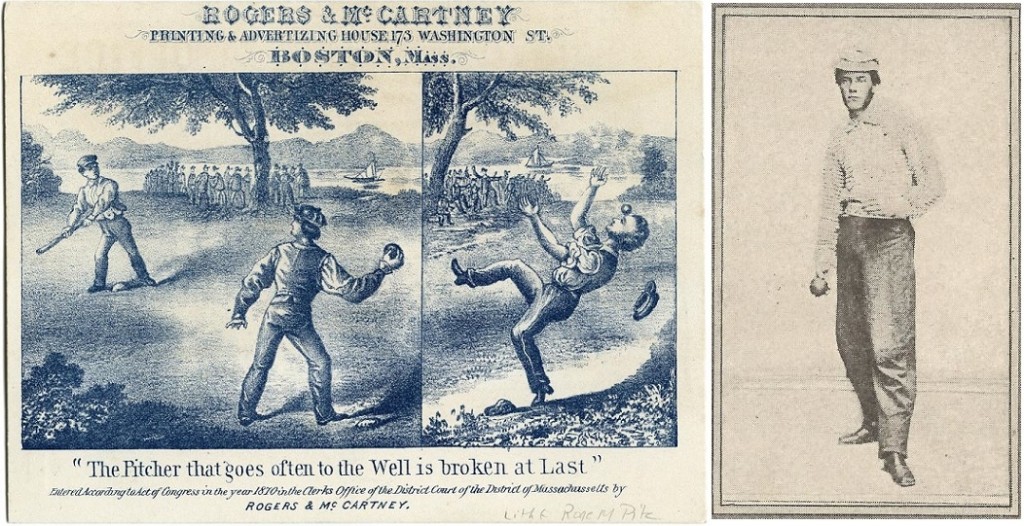

In 1866 Rogers relocated to Massachusetts to play for the champion Lowell Club and in 1867 he was also named the NA’s first vice president. Within a few years by 1869 Rogers established himself as one of the game’s earliest entrepreneurs when he self-published the New England Chronicle, a weekly sporting newspaper that devoted considerable space to the National Pastime. A printer by trade, Rogers was unable to sustain his newspaper endeavor and after the paper folded in 1870 he partnered with another printer and founded the Rogers & McCartney Printing Advertising House at 173 Washington Street in Boston. Evidence of the venture was found in the collection of the Library of Congress by John Thorn in the form of a woodcut produced by Rogers which incorporates a baseball scene entitled, “The Pitcher that goes often to the Well is broken at Last.”

Clik here to view.

John Thorn discovered this baseball-themed woodcut produced by Rogers & McCartney in 1870; Mort Rogers (right) was a printer by trade and operated his printing business while playing for the Star Base Ball Club and umpiring Red Stocking games in Boston.

By 1871, Rogers re-named his printing venture “Rogers & Fitts” at the same address and also umpired games for Harry Wright’s Boston Red Stockings in the brand new National Association. It was during that same year that Rogers designed and manufactured what he described as a “Base Ball Photographic Card” that featured an oval portrait of a professional ballplayer pasted onto an ornately designed lithographic card with baseball motifs that doubled as a score card. As evidenced by Thorn’s 19th century newspaper discoveries, the entrepreneur set out on an ambitious mission to disseminate his photographic cards all over the country at ballparks and baseball emporiums including the sporting goods houses of Peck & Snyder in New York City and George B. Ellard in Cincinnati. While the evidence shows that Rogers & Fitts published their scorecards from 1871 through 1872, little is known about the firm’s production numbers and sales figures. The only financial records we could find were related to Rogers’ partner, Frank E. Fitts, of Lowell, who filed for personal bankruptcy in August of 1871 and had that action discharged as of March 27, 1872.

Clik here to view.

This Rogers & Fitts score card from May 31, 1871 includes notices from Mort Rogers telling fans that his new photographic cards would be available for the June 2nd game vs. Chicago. The score card also revealed that Rogers' first card was sold at the ballpark on May 20th (Boston Athenaeum Collection).

One clue providing a window into the operation of Rogers’ printing business was also uncovered by John Thorn. MLB’s official historian discovered, in the collection of the Boston Athenaeum, a scorecard published by Rogers & Fitts for a May 31, 1871, game between the Red Stocking and Forest City clubs that pinpoints when the card business launched in Boston. The scorecard included a notice from Rogers informing fans that his photographic card, which was first introduced at the Boston Grounds on May 20th, was not ready for sale due to the “great labor needed in getting it done handsomely.” Rogers assured the fans that the cards would be ready for the June 2nd game scheduled against Chicago and added that the scorecard would again depict Harry Wright (Card No. 1) by popular demand.

Clik here to view.

An 1871 ad in the NY Clipper (left) reveals that Peck & Snyder sold team trade cards featuring the Reds of 1869 and the Atlantics of 1868, but also documents how the Mort Rogers score cards were marketed as photographic cards that featured the pictures of NA players on seven teams including Levi Meyerle of Philadelphia (center).

An 1871 Peck & Snyder advertisement discovered by Hauls of Shame in 2013 sheds even more light on how the company’s scorecards were marketed throughout the country. Originally the ad was noted for its inclusion of the Peck & Snyder trade cards of the Red Stockings and the Brooklyn Atlantics but a second look at the ad reveals more evidence confirming Thorn’s discoveries and goes even further to show that the Mort Rogers cards may have been the game’s first true set of commercially sold baseball cards. The newspaper reports unearthed by Thorn show that Mort Rogers distributed the cards to ballparks in the eastern states and in the west and the 1871 Peck & Snyder ads confirm that the cards were also distributed to and sold at retail establishments that had accounts with Rogers & Fitts. The ad also documents that Rogers created cards for (43) players on Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia and Washington and about (30-34) more unidentified players for Cleveland, Rockford and Kekionga—seven of the nine teams Rogers planned to create according to the news item in the Cleveland Ledger on July 13. Curiously absent from the Peck & Snyder ad are the photos of the players on the Haymaker Base Ball Club of Troy, New York. Which leads us to another interesting discovery via John Thorn.

Just one week after Mort Rogers packed up his scorecards and took them on the road to sell at the ballparks in the Midwest, the following item ran in the Troy Daily Whig on July 22nd:

“The members of the Haymaker Club yesterday had two group pictures taken. Each member also had a picture taken, copies of which, with score card ruling upon the backs, are to be sold at the different games of the club, the picture of each member to be sold in regular order at the successive games.”

Just two weeks after Rogers’ plans to create photographic cards depicting every single player in the National Association was published in the Cleveland papers, it appears that the Haymakers co-opted his idea and decided to create their own cards sponsored by the Burr Penfield Cigar Store in Troy.

Clik here to view.

The Troy Haymakers of 1871 created their own player scorecards just weeks after Mort Rogers announced his plans to create a photographic card for each player in the NA. The Troy scorecards were sponsored by cigar store owner Burr Penfield.

Penfield was the brother of third baseman Carroll “Cal” Penfield who hailed from Troy and played for local teams including the Enterprise and the Putnams before he joined the Haymakers in 1866. The Burr Penfield “Photographic Cards of the Haymakers” were printed by a local outfit called Hurley Brothers Printers with offices located on the same block as Penfield’s cigar emporium. It remains a mystery why the Haymakers were the only club who decided to create their own locally issued cards rather than be part of Rogers’ distribution at ballparks and stores throughout the country. It is also unclear why Rogers did not include Boss Tweed’s Mutual Club of New York City in his series but what is clear is that Rogers had to rely on the work of J. W. Black and out of town photographers to provide him with albumen prints of player portraits. As Thorn also noted, many of the portraits used by Rogers are identical to those incorporated into the 1871 team composite CDVs made by J. A. Pierce Co. in Chicago.

Clik here to view.

Mort Rogers' 1872 scorecard of Count Sensenderfer of the Philadelphia Athletics features a portrait identical to the one appearing in the 1871 A's team composite (right) sold by J.A. Pierce & Co. in Chicago.

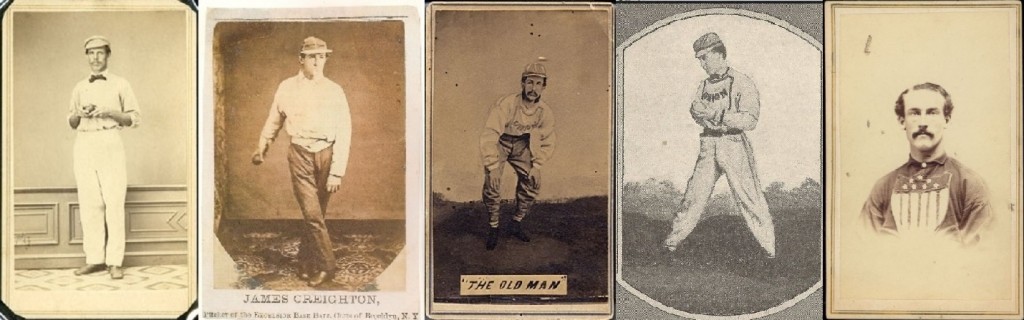

The question as to what constitutes the first baseball card or the first baseball card set has long been a hot button topic among hobbyists, baseball researchers, dealers and auctioneers. For many years the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings trade card issued by Peck & Snyder was considered the first baseball card and in more recent times competing claims have been made in support of the c.1870 memorial trade card of pitcher Jim Creighton; the 1863 cricket-ticket CDV cards produced by Harry Wright; the 1865 CDV cards featuring Charlie Pabor and Dave Birdsall of the Union BBC of Morrisania; and the “set” of 1866 player CDVs of the Unions of Lansingburgh team created by E. S. Sterry.

Clik here to view.

Claims for "first baseball card" have been made for (l to r): an 1863 CDV cricket-ticket of Harry Wright; a memorial trade card featuring Jim Creighton; CDVs of Union BBC players Birdsall and Charlie Pabor and a "set" of 1866 player portrait CDVs of the Union of Lansingburgh team.

Each time these photographic cards have surfaced at auction for sale, auctioneers have pled their case for the “first baseball card” hoping to bolster bidding and in several cases the sales job worked. In particular, the claims that the 1863 Harry Wright cricket CDV produced by Jordan & Co. was ”the world’s very first baseball card” and that it was “the first card picturing a baseball player printed for the purpose of promoting the retail sale of a product to the public” propelled bidding into the high five-figures as Keith Olbermann paid $83,000 to secure the card at MastroNet/REA in 2000. In 2008, REA sold for $8,812 a c. 1865-70 CDV of Dave Birdsall which featured within his image the caption of his nickname “The Old Man.” In its lot description REA claimed: “To the best of our knowledge, Birdsall’s card is the very first baseball card with the identification of a current individual player incorporated into the design of the card. By this definition, the “The Old Man” card can lay claim to being the first baseball card.” Another card of Birdsall’s teammate, Charlie Pabor, was also issued with the nickname “The Old Woman In The Red Cap” within its image and was featured in A.G. Spalding’s 1911 book America’s National Game and is currently missing from the New York Public Library’s Spalding Collection.

Disputing these earlier claims to the “first baseball card” is dealer Brian Wentz of BMW Cards in Wisconsin who is currently offering for $179,000 a set of 1866 player CDVs featuring the Unions of Lansingburgh. According to Wentz all of the other alleged first cards “cannot be definitively dated to 1866 or earlier and those that can do not comprise a complete set or subset of a specific team — i.e., they were not meant to be collected as baseball cards. In our opinion then, this group of six different players from the 1866 Union team of Lansingburgh would represent the earliest known baseball cards.”

There are many conflicting opinions as to what constitutes the oldest or first baseball card or card set. John Thorn told us he considers the first baseball card an 1844 engraved ticket for the ball of New York City’s Magnolia Ball Club which incorporated a scene of a baseball game in progress on the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey. Card collectors and purists, however, require cards to meet a host of different criteria to be considered the first card or the first set. Considering the new information he has added to the debate regarding the Mort Rogers cards Thorn told us, “I would agree that the Rogers scorecards, printed in unknown quantities, is the first numbered set of baseball players.”

Clik here to view.

A strong case could be made that the Mort Rogers cards were the first true baseball card set and that they incorporate the elements present in most every classic baseball card issued since the 1880's including (clockwise) N-167 Old Judge (1886); N-172 Old Judge (1888); T-206 (1909); M-101 (1915); Cracker Jack (1915); Goudey (1934); Topps (1952) and Topps (2014).

Back in 2013, an 1860 CDV of the Brooklyn Atlantics was erroneously characterized by the mainstream media as the first baseball card and in response Keith Olbermann laid down his own ground rules for what actually constitutes a baseball card. Olbermann pointed to the c.1869 Peck & Snyder team trade cards of the Reds and Atlantics but said that “the truly big idea for baseball cards, the seemingly obvious one- make lots of cards of lots of different players” didn’t appear until the Kalamazoo Bat and Old Judge cards were sold in Goodwin Tobacco cigarette packs in 1886. Olbermann did refer to the Mort Rogers cards for featuring individual players but noted that they were only sold at Boston games and that Rogers “lost his shirt” in the endeavor.

Clik here to view.

Each Mort Rogers "Baseball Photographic Card" features a player portrait and identifies each subject by name, team, position and number in the series (all in red). This sequence shows players from the Boston, Philadelphia and Washington teams numbered from 1 to 48. (L to R.): Harry Wright, Boston #1; Levi Meyerle, Phila. #16; Davy Force, Wash. #29; Cal McVey, Boston #48.

Contrary to Olbermann’s opinion, however, the new information discovered by John Thorn about the sale of the Mort Rogers score cards nationally and the evidence from 1871 showing that Peck & Snyder marketed them more as “baseball photographic cards” than as just “score cards,” creates a strong case for the Rogers issue as the first true baseball card set. Minus the portrait cards of the Haymakers and the Mutuals, the evidence shows that the cards featured all of the players from seven of the nine National Association teams and that each one was numbered in what the Cleveland Leader called a “series” that would “make a valuable collection.” The evidence suggests that these photographic cards were produced in great quantities to service large crowds in multiple cities and were intended to be collected. As demonstrated on the recent Antiques Roadshow episode, it appears that at least one 19th century fan did just that as he saved the cards and displayed them in an album that was retained by his own family for over 140 years.

Clik here to view.

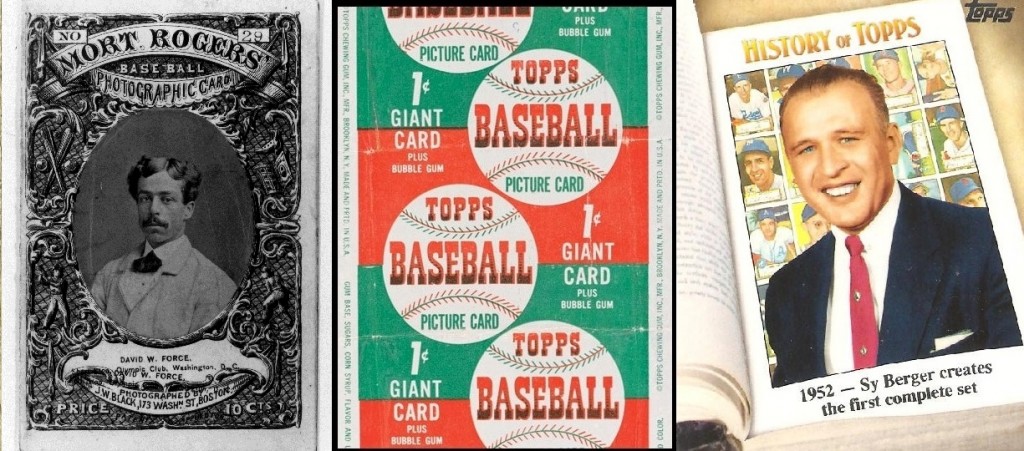

In 1871 Mort Rogers called his product "Base Ball Photographic Cards" while Sy Berger (right) and Topps marketed their product as a "Baseball Picture Card" as seen on a 1952 wrapper (center).

When former Topps vice president Sy Berger passed away in December he was hailed as the “Father of the Modern Day Baseball Card.” Berger joined Topps in Brooklyn in 1951 and a year later he worked with hobby legend Woody Gelman to create the iconic 1952 Topps set featuring 407 cards of every player in the American and National Leagues. Berger was widely credited with creating that first complete set and incorporated design elements featuring facsimile player autographs, team logos and statistics on the backs of the cards picturing Mays, Mantle and Jackie Robinson. In his obituary in the New York Times Berger was remembered as the man who “conceived the prototype for the modern baseball card.” It is interesting to note also that Topps and Berger marketed their creation as a “Baseball Picture Card” (as Bowman also did dating back to 1948), a designation so very similar to Rogers’ own “Base Ball Photographic Card.”

The former Brooklynite, Mort Rogers, came up with his scheme to peddle baseball cards more than eight decades before Sy Berger’s arrival at Topps. Rogers designed his own prototype for baseball cards and worked to create his own ground-breaking near-complete set of cards picturing the game’s true pioneers including the Wright brothers, Albert Spalding and Al Reach. Rogers’ “invention” was the product of his design skills as a printer and there’s no doubt he was way ahead of his time. As evidenced, an argument could even be made that it was Rogers who first coined the term “baseball card.” His 1871 card/scorecard issue also introduced some of the very same elements that Berger and other card pioneers like Woody Gelman had used dating back to the Goudey Gum issues of the 1930s. Every one of his cards had a uniform design and included the picture, name, team and position of each player.

Clik here to view.

The Mort Rogers scorecards are not recognized in the Standard Catalog of Vintage Baseball Cards (left and center). The 1872 Warren CDV photos of Harry Wright and the Red Stockings (right) are included as baseball card issue/series.

In his own obituary, there was no mention of Mort Rogers’ baseball card creations and innovations along with the tragic details of his demise. Rogers passed away just three days after his own brother Fraley Rogers (a former Boston Red Stocking player) had committed suicide and reports stated that the printer’s brother had killed himself after he’d contracted malaria and was driven to a state of temporary insanity. Mort Rogers’ death in New York City on May 13, 1881, was attributed to his shock over his brother’s devastating suicide.

Outside of his being mentioned in auction catalogs beside each surviving “baseball photographic card” bearing his name, Mort Rogers has, for the most part, been forgotten and never properly credited for his printing innovations and his baseball card designs. The Standard Catalog Of Vintage Baseball Cards doesn’t even recognize the “1871-72 Mort Rogers Scorecards” as a baseball card issue although it does include the 1872 Warren CDV portraits of Harry Wright’s Red Stockings as an actual card series. All things considered, if Sy Berger is remembered as the “Father of the Modern Baseball Card” it may be time for Mort Rogers to receive his just due as the “Grandaddy of the American Baseball Card.”

(Editor’s Note: Although these discoveries add to the history of the Mort Rogers Scorecards there is likely much more information about the cards that has yet been unearthed. If you know of or find any new information about the cards, or know of previously unknown examples to add to the population please contact us at: Tips@haulsofshame.com)