|

Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  Letters to HOF founder Stephen Carlton Clark, an heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, appear to have been stolen from the NBL. His granddaughter, Jane Forbes Clark (inset), the current Chairman of the HOF, has been silent on the issue of the thefts. |

It’s been a few years since a Haulsofshame.com investigation revealed that a large cross-section of papers donated to the Baseball Hall of Fame by Commissioner Ford Frick had been wrongfully removed from the National Baseball Library and were subsequently sold on the “black market” for baseball artifacts. That being said, there was no mention of that scandal in the glowing profile about Hall Chairman Jane Forbes Clark published yesterday in the New York Times.

In his Times profile, writer Richard Sandomir failed to mention anything about the massive thefts and also chose not to reference another 2013 report about the Hall of Fame thefts which uncovered additional proof showing that documents from Cooperstown’s internal files have also been compromised. Our report showed evidence in past auction offerings of letters addressed to Hall of Fame officials including one written in 1946 by Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie, which was sold by Huggins & Scott.

Earlier this year, Clark and Hall President Jeff Idelson failed to respond to our Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) request related to the sale of a stolen 1909 Pittsburgh Pirate photo and now a new discovery shows that yet another letter sent by Lajoie to the Hall of Fame appears to have been stolen from the museum’s internal files. This letter, however, was sent to Jane Clark’s own grandfather and Hall of Fame founder, Stephen Carlton Clark.

The letter Lajoie wrote in 1947 was a thank you for a birthday telegram that had been sent to him by Clark, an heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune and one of the richest men in America. The letter appeared in a 2006 Hunt Auctions sale of baseball memorabilia and sold for close to $2,000. The significance of the letter went unnoticed at the time, but its inclusion in the auction was clear-cut evidence suggesting that files related to the Hall’s founder have also been compromised as part of the multi-million dollar heist of baseball documents from the National Baseball Library in Cooperstown.

Clark financially backed the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum concept after it was presented to him by his employee, Alexander Cleland, in the Spring of 1934, and his own baseball artifacts and lithographs served as the nucleus of the fledgling institution’s early collection. With the assistance of Cleland, Clark enlisted the support of Ford Frick and organized Baseball itself, and the museum formally opened during Baseball’s Centenial celebration in the Summer of 1939. When the museum first opened its doors it attracted thousands of visitors but by the time Clark passed away in 1960 the institution was hosting hundreds of thousands of visitors making pilgrimages to what had become known as baseball’s shrine in the tiny village of Cooperstown.

In addition to founding the Hall, Clark was also a world renowned collector of art who, along with his brother, Robert Sterling Clark, amassed one of the finest collections of paintings ever held in private hands. Clark helped found the Museum of Modern Art in New York City with Nelson A. Rockefeller and also served as MOMA’s Chairman of the Board. Clark also served as a trustee at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he bequeathed a large portion of his collection which would today be valued at close to a billion dollars. The remainder of his collection was left to Yale University including the famous Van Gogh painting, The Night Cafe, which alone is currently valued at close to $150 million. However, despite his renowned philanthropy and collecting, when the New York Times published his obituary in 1960, he was remembered more for having put on display the misshapen and time-worn ball that was said to have been used by Abner Doubleday on what the Times then reported was the “field where baseball is believed to have originated in 1839.”

Most recently Clark’s name has been in the news regarding another theft-related issue in which his acquisition of Van Gogh’s The Night Cafe has been the subject of litigation. Clark has been accused of originally obtaining the painting illegally as looted artwork via a money laundering scheme. Pierre Konowoloff, a descendant of Russian industrialist Ivan Morozov filed a lawsuit against Yale University claiming that the Van Gogh painting Clark bequeathed to the school in 1960 was stolen from his family by the Bolsheviks during the Russian revolution. Konowaloff claims that Clark was aware the painting was stolen property when he purchased it from the legendary Knoedler Galleries in New York City in 1933. (In 2011, Knoedler closed its doors after several lawsuits were filed accusing the gallery of selling fakes.) Yale also filed suit against Konowaloff to block him from claiming ownership of the famous painting. In March of 2013, Konowoloff’s attorney, Allen Gerson, filed an affidavit stating he was approaching Russian officials to see “whether the sale of The Night Cafe to Stephen C. Clark conformed to then prevailing Russian law and policy” and whether the controversy over the painting would have any impact on the Russian Federation’s “relationship with the United States.”

Clik here to view.

This letter written by HOFer Nap Lajoie was sent to millionaire Stephen C. Clark in 1947 and then sold in 2006 at Hunt Auctions in Exton, PA.

In stark contrast to his multi-million dollar artworks, the $2,000 purloined letter sent to Clark by Hall of Famer Napoleon “Larry” Lajoie was simply a thank you letter to the officers and directors of the museum for sending him a birthday telegram. The letter appeared as lot 742 in Hunt Auctions’ February 2006 sale and sold for a hammer price of $1,600. Hunt’s auction description mistakenly described it as “regarding an invitation to the Hall of Fame.” Such a letter, written to the then Hall of Fame President would be maintained in the files of either the National Baseball Library or the family papers of Jane Forbes Clark. To the best of our knowledge, Clark has not sold or dispersed her grandfather’s papers and such a letter written to the president of the Hall of Fame would be property of the museum and library, which operates as a 501 (c) (3) educational institution and public trust under the jurisdiction of the Attorney General of New York State.

In the past, Jane Clark has actually reclaimed and purchased Hall of Fame correspondence that had ended up in private hands. In 2007, she purchased at Sotheby’s several letters written by Hall of Famers to her grandfather’s employee, Alexander Cleland, which were once part of an archive preserved by his family known as The “Cleland Papers.” After he retired in the early 1940s, Cleland took his files that contained documents and letters related to the founding of the Hall. The entire collection, consisting of hundreds of documents, sold at auction in 1996 but the 2007 offering included only a handful of letters.

Those letters were written to Cleland by Lajoie and fellow Hall of Famers like Honus Wagner, Cy Young, Tris Speaker, and Ford Frick and were purchased personally by Clark for close to $60,000. Clark paid $6,600 for the one lot featuring a Lajoie letter. Clark told reporters after the sale, “My grandfather founded the Hall of Fame, and these papers are important to my grandfather, and to the Hall of Fame in terms of being some of the original documents that began the Hall of Fame as we know it today.” When asked by Sports Collectors Digest how these documents ended up into private hands in the first place Clark responded, “We’re not entirely sure, but we think that when Mr. Cleland left he took boxes of documents with him. And those have been, we think, with his family and we are very happy to get them.” Clark’s response appeared to suggest that it was the Hall’s contention that Cleland had no right to remove those papers from his office when he retired in 1941.

Clik here to view.

Hall of Fame Chairman, Jane Forbes Clark, purchased several letters related to the founding of the Hall of Fame for over $60,000 at Sotheby's in 2007.

Before the entire Cleland collection was sold at auction at Christie’s in 1996, author James Vlasich utilized them as a resource for his book, A Legend For The Legendary and presented a complete copy of the Cleland Papers to the National Baseball Library where they are now available for historians and researchers. We have verified that the 1947 letter from Lajoie to Stephen C. Clark was never part of the Cleland Papers collection.

Haulsofshame.com has also obtained a copy of another letter sent to Stephen Clark by Ty Cobb in 1948. The body of the letter was written by Cobb’s wife but signed by Cobb, himself, and thanks Clark for sending him a framed photograph of his Hall of Fame plaque. In addition, Cobb mentions to Clark his regrets in not being to donate more “mementos, uniforms, shoes etc.” He wrote, “I was unable to do what I would like to have for I had just given them away to boys who had asked for them, also the moths got some of the uniforms.” The letter does not currently appear on the NBL’s ABNER database as part of the correspondence collections and is also suspected to have been wrongfully removed from the institution. The NBL files at Cooperstown still include other letters sent to Clark from Japanese baseball fans and one from J. G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News asking Clark to induct President Franklin Delano Roosevelt into the Hall of Fame.

Clik here to view.

Ty Cobb sent letters to Stephen Clark (left) and Hall President Paul Kerr (right). All of the letters are missing from the Hall and believed to have been stolen from the museum's internal files.

The Cobb letter sent to Clark is similar to other letters Cobb wrote to his right-hand man, Paul Kerr, who became Hall President after his death in 1960. The Cobb letters to Kerr, which were usually lengthy missives, have appeared for sale in virtually every major baseball auction dating back to the early 1990s. Like the letters to Clark and the scores of other letters written to other Hall officials, the Kerr letters are believed to have been stolen from the NBL.

We called Jane Forbes Clark several times earlier this year at her Clark Estates offices in Rockefeller Center to inquire whether her family had ever sold or liquidated any of her grandfather’s correspondence or personal papers, and whether the family maintains a collection of papers that have never been made available to the public. There were no special provisions in Stephen C. Clark’s will to seal or restrict access to his surviving papers and letters. We also called Clark to inquire as to whether the handful of letters appearing on the NBLs ABNER database were the only Clark related documents housed at the Hall of Fame. Clark did not respond to our inquiries.

We also called and sent emails to Hall of Fame’s Director of Communications, Brad Horn, to see if he had any explanation as to how an internal museum document like the Clark letter could end up in a Hunt Auctions sale? Horn did not respond to our multiple inquiries either.

Clik here to view.

The Clarks of Cooperstown by Nicholas Fox-Weber is the definitive biography of Stephen C. Clark. Clark owned Van Gogh's painting, "The Night Cafe" and left it to the Yale University Art Museum.

Correspondence either to or from Stephen Clark is exceedingly scarce and only a very limited quantity of documents have been made available to researchers and authors. Clark’s biographer, Nicholas Fox Weber, author of The Clark’s of Cooperstown, told us that the only correspondence he found in the course of his research was found in the files of the Museum of Modern Art, the Clark Institute and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In particular, the Met’s archive notes specifically on its website its objective to “preserve in perpetuity” the “official correspondence of the Museum, to make the collection accessible and provide research support, and to further an informed and enduring understanding of the Museum’s history.” Considering Clark was involved intimately with both institutions, it appears the Cooperstown archive did not adhere to the same standards as the Met.

When Weber inquired of long-time Clark representative, and former Hall president, Ed Stack, as to whether the family maintained their own archive of Clark papers, Stack “politely declined his request.” Weber did, however, have the rare opportunity to interview Clark’s granddaughter Jane.

Although Clark cooperated with Weber, some controversy ensued when the book was released and the Met chose not to include it in the museum bookshop. According to The New York Times, Weber’s editor was told “that some eyebrows at the museum had been raised by the book’s undercurrents of gay behavior.” Publishers Weekly reported, “Someone at the Museum didn’t like the references to Alfred (Corning) Clark’s double life.” Weber’s research of Jane Forbes Clark’s great-grandfather revealed that Alfred Corning Clark engaged in several homosexual relationships while still married and raising a family. Weber told the Times the Met’s actions qualified “completely as censorship” and added, “Why the Met in 2007 would be so put off by this element of the book is astonishing.”

Clik here to view.

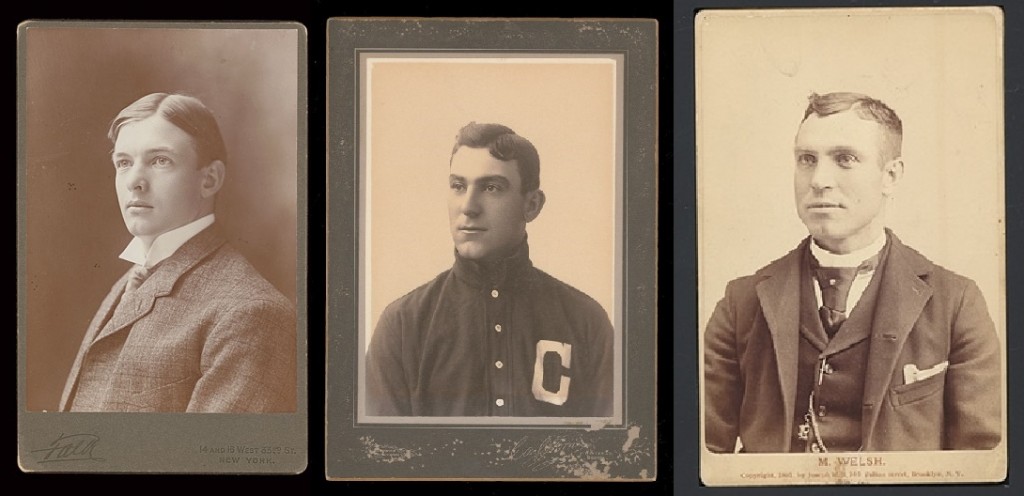

Clear cut evidence of the magnitude of the HOF thefts are these three rare cabinet photos which were identified as HOF property when offered at auction. Sources indicate that at least two of these gems featuring HOFers Christy Mathewson, Nap Lajoie ans Smilin' Mickey Welch have been returned to Cooperstown. Each photograph has an estimated value between $10-20,000.

Jane Clark’s silence related to the Hall of Fame thefts is stunning considering the findings of investigations conducted by Haulsofshame.com over the course of the past three years illustrating the magnitude of the heist of documents and photographs from the NBL. In a 2012 article published by Deadspin, we identified another Lajoie-related item that was stolen from the Hall of Fame and offered for sale at Heritage Auction Galleries in Dallas, Texas. It was a rare Carl Horner cabinet photograph of Lajoie that had a vandalized library accession number and other identifying marks showing it was Cooperstown’s property. At the time the article was published the photo already had a bid of $4,250 and Heritage estimated it would sell in excess of $15,000. Heritage withdrew the photograph from the sale less than an hour after the article was published. Other stolen photographs of Christy Mathewson and Smilin’ Mickey Welch valued at over $10,000 each were identified in sales at Mastro Auctions and Robert Edward Auctions and have since been returned to Cooperstown.

In addition to the 1947 Lajoie letter addressed to Stephen C. Clark, documents and correspondence originating from the August Herrmann Papers and Frederick Long Papers collections have also appeared for sale both publicly and privately. The appearance of these documents for sale, with no mention of provenance whatsoever, illustrates further how severely the National Baseball Library’s collections have been compromised. The sale of the Lajoie letter has been reported to the Cooperstown Police Department and an incident report has been filed along with several others recently filed by Chief Michael Covert for stolen items ranging from an 1870 CDV photograph of the Philadelphia Athletics to an 1886 cabinet photograph of the New York Giants.